It’s nonflexible to know for sure how Abdellatif Kechiche felt when, for the first time in the history of the Cannes Mucosa Festival, the Palme D’or was awarded not just to him and his film, Blue is the Warmest Colour, but moreover to the two lead actresses, Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulous. He was certainly quick to lash out at them when they criticised his harsh working methods, expressly Seydoux who, in an op-ed for Rue89, he tabbed an opportunist that was “fine-tune[ing] her image […] in uncounted calculated interviews”.

Kechiche complained that his mucosa was “sullied”, but despite some criticism, most notably a blog post from Jul Muroh, the writer-artist of the source comics, the success of Blue was exceptional. It ended 2013 on myriad best-of-the-year lists, coming third in both Cahier du Talkie and Sight & Sound’s collated lists. Now, ten years later, Kechiche’s career has truly been sullied, and plane his most well-known mucosa looks vitally different.

Blue’s graphic lesbian sex scenes, between Exarchopoulos’ Adèle and her first love, Seydoux’s older, confidently ‘out’ Emma, were certainly controversial at the time. Muroh tabbed them “brutal and surgical”, like lesbian porn made for a straight audience. But few today would dare undeniability them passionate or frank, as many reviews did. Their lattermost length, leering camera and ignorance of the mechanics of sex have made them maybe the textbook example of the male gaze; they are a total fantasy shot with the tropes of realism.

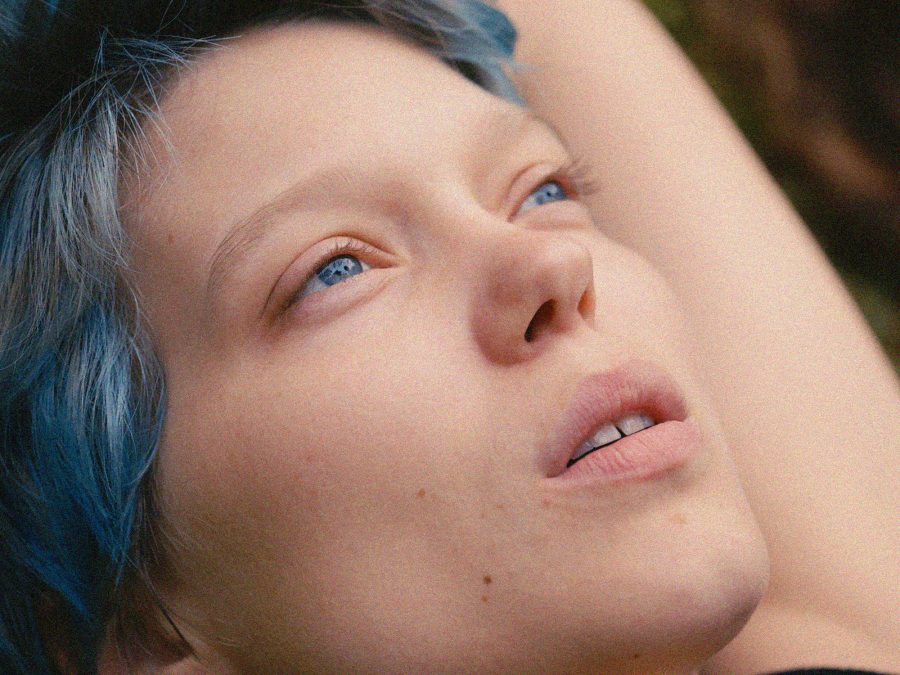

Kechiche’s style is just a thin veil obscuring his desires from the regulars and from himself. He seems to believe that holding a camera tropical unbearable to someone’s squatter – usually Exarchopoulos’ – for long unbearable (both in terms of the scenes and the shoot) will naturally capture something real, as if totally ignorant of the pressures and projections he brings. That which makes every scene, as J. Hoberman said of the sex scenes, “a menage a trois involving the actors and the camera”. The mucosa isn’t told from Adèle’s perspective as it purports to be – it’s told from Kechiche’s.

His intrusions proffer vastitude the characters, as Seydoux and Exarchopoulos discussed in an interview with the Daily Beast. Without shooting a hundred takes of Adèle and Emma crossing the street and exchanging their first glance, Seydoux couldn’t help but giggle, to which Kechiche “became so crazy that he picked up the little monitor [..] screaming ‘I can’t work under these conditions’”. Anyone taking his vision, for what is ultimately quite a silly scene of love at first sight, with anything less than total seriousness and submission is treated like an abuser. Unsurprisingly, when Exarchopoulos cut herself and was “bleeding everywhere and crying with her nose running”, Kechiche said she needed to do flipside take.

Seydoux temporarily stepped when from this interview in early 2014 when she told the Evening Standard “I love his talkie […] the way he treats us? So what!” This wasn’t an uncommon defence, the ways are justified by the ends. But Kechiche undoubtedly damaged the performances, while there isn’t a moment where anyone is less than totally convincing, a weft built only in close-up lacks context. They don’t exist outside of what happens to them, outside of what he does to them. More importantly though, some things can’t be justified by any performance, and Kechiche would navigate that line in his follow-up: a trilogy of films that would destroy his career in a way that no new perspective on Blue overly could.

Mektoub, My Love was troubled from the start, with producers pulled out without learning that it was going to be split into three parts, and Kechiche had to sell his Palme to well-constructed the first two: Canto Uno in 2017 and Intermezzo in 2019 (both of which played Cannes). In them all his worst tendencies are expanded: the sketchiness of Blue’s arc from first love to heartbreak turns to total plotlessness, the ogling of women becomes the unshortened point, and the sex scenes not only grow longer, but are shot unsimulated rather than with the use of prosthetic genitals. The lead actors, Ophélie Bau and Shaïn Boumédine, were uncomfortable with this, but, to quote an unrecognized report published in Midi Libre in 2019, “by the way of insistence, and over time and with swig stuff regularly consumed, [Kechiche] managed to get what he wanted.”

It’s nonflexible to oppose that there aren’t unconfined directors who see themselves in the lineage of the unconfined male versifier that sits at a typewriter (or camera) and bleeds, that bares his soul on screen and on set. But Kechiche shows this idea, stripped of pretences and other merit, for what it really is: an excuse to enact power, often in a gendered way, torturing a performance from an actress as if she was incapable of doing it herself. Kechiche mockingly, maliciously flaunts this in one of Blue’s first scenes, when an off-screen voice, a male teacher, directs one of his sexuality students to read aloud this passage: “I am a woman and I tell my story”.

Today, the third Mektoub mucosa remains in limbo and Intermezzo hasn’t received a wide release since its first two screenings at Cannes. It’s tempting to think that this story is one of justice that illustrates how far we’ve come in the last ten years. This year, when reports came out well-nigh harassment by the director and inappropriate behaviour by the hairdo on the set of Catherine Corsini’s Le Retour, Cannes pulled it from the competition spot it was once promised. As was moreover reported in Variety, Corsini widow a masturbation scene featuring the fifteen year old lead actress to the script and filmed it without informing the government soul that legislates underage performers, causing some of the film’s funding from the CNC, France’s national mucosa board, to be revoked.

But the president of the CNC, Dominique Boutonnat, has held his position plane while stuff investigated for sexual assault. And surpassing Corsini and her producer responded, denying any claims of vituperate and including a statement from Gohourou, but whereas that they should have reported the same scene, her mucosa was widow when to the official selection. In less than two weeks the whole situation was resolved, all due diligence had theoretically been done.

There seemed little uneasiness in announcing the festival’s opening film, Jeanne du Barry, the first to star Johnny Depp since his divisive trial versus Amber Heard which, in and of itself, made the wins of MeToo finger precarious. To me, it felt like the end of something. If a woman is less than a perfect victim, Depp, his lawyers and myriad TikToks told us, if she so much as raises her hand, she isn’t plane complicit, she is the real abuser. The most prestigious mucosa festival in the world seems to stipulate (and if you don’t, well, protests have been banned, I’m afraid).

Maybe Mektoub My Love’s final part is too sullied, but the only real difference between the series and Blue is the Warmest Colour is that the latter, to quote the speech Steven Speilberg gave when awarding it the Palme, “made all of us finger like we were privileged […] to be flies on the wall”. It created a inveigling facsimile of prestige, like a scene in a gallery that framed the pulp sex scenes within the tradition of nude painting, which obscured, or for some plane justified, Kechiche’s cruelty and desire.

.webp)